Desmond Tutu’s Life and Legacy

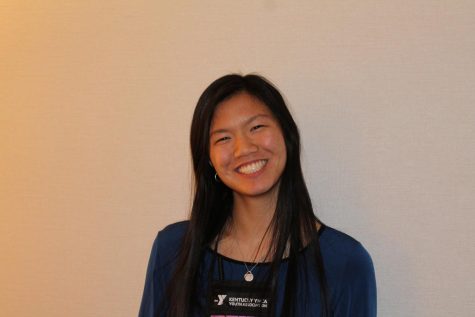

Archibishop Desmond Tutu at the Deutscher Evangelisher Kirshentag in Cologne, Germany (2007)

February 7, 2022

He loved, he laughed, he cried, he was forgiven, he forgave words by which Archbishop Desmond Tutu hoped to be remembered. On December 26, 2021, the global advocate and 1984 Nobel Laureate, most known for his anti-Apartheid work, died in Cape Town, South Africa. As the world deals with the loss of a historic figure, it also reflects on his legacy and work.

Born in 1931 in Klerksdorp, South Africa, Desmond Tutu dealt with a South Africa heavily influenced by its extensive colonial history. He faced systemic racism and inequality as a black South African living in a society dominated by a white minority. In 1948, the government, controlled by the white minority, began Apartheid. Apartheid, Afrikaans for separateness, was legal, race-based segregation, similar to Jim Crow in the U.S. By limiting rights, it was a practice intended to preserve the power of the white minority. In the following decades, it would be met with resistance. Among the leaders of this movement were Nelson Mandela and Desmond Tutu.

Unlike Mandela, who was a lifelong advocate, Desmond Tutu was first a teacher and then an Anglican priest.

He began teaching in 1955, following in the footsteps of his father. However, in 1957, he left this field to become ordained in the Anglican faith. He attended St. Peter’s Theological College in Johannesburg, South Africa, and became a priest in 1961. He left South Africa the following year to pursue an M.A. at King’s College London, which he obtained in 1966. From 1972 to 1978, Tutu held leadership positions within the church, eventually moving back to serve in South Africa and Lesotho. In 1978, when he was appointed the general secretary of the South African Council of Churches, he became a vocal advocate for Black South African rights.

Throughout the 1980s, Tutu spoke widely and publicly about the issues facing Black South Africans under Apartheid. He was a vocal proponent of non-violent protest, becoming one of the leading figures in the economic boycott of the South African government. His role within the movement was vital, bringing international and economic pressure for change. Many credit the pressure caused by these boycotts as the reason apartheid ended in 1990.

In 1984, he won the Nobel Peace Prize for his activism and leadership. This honor signified the international pressure to end Apartheid. The following year, Tutu became the first Black Anglican bishop in Johannesburg, and in 1986, he was elected as the first archbishop of Cape Town, South Africa. He continued his work into the 1990s as South Africa began its democratization.

In 1996, Tutu was appointed by Pres. Nelson Mandela as the head of the Truth and Reconciliation Committee with the purpose of investigating the alleged human rights violations committed under Apartheid. In the same year, Desmond Tutu retired as Archbishop Emeritus, maintaining the title of Archbishop as an honor rather than a position. In 1998, the committee released its final report, containing 3,500 pages, detailing its findings on the atrocities and violations committed during Apartheid. In 2007, he co-founded the Elders, a group of world leaders whose purpose is to address human rights abuses. In 2009, Desmond was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by then U.S. President Barack Obama.

In the wake of Desmond Tutu’s death, the world reflects on his mission to create a more equitable world. Tutu is honored for his diligent work, which has significantly contributed to global social progress. Beyond racial justice, he was a champion for the environment, women’s rights, and LGBTQ+ rights. He was a continual critic of the government and the ways in which it perpetuated inequality. Cape Town will light up Table Mountain, the city’s landmark, in purple, reflecting the color of his robes. Tutu will lie in state at St. George’s Cathedral in Cape Town and then undergo aquamation, an eco-friendly alternative to cremation.