The Chicago Tylenol Poisonings

March 11, 2022

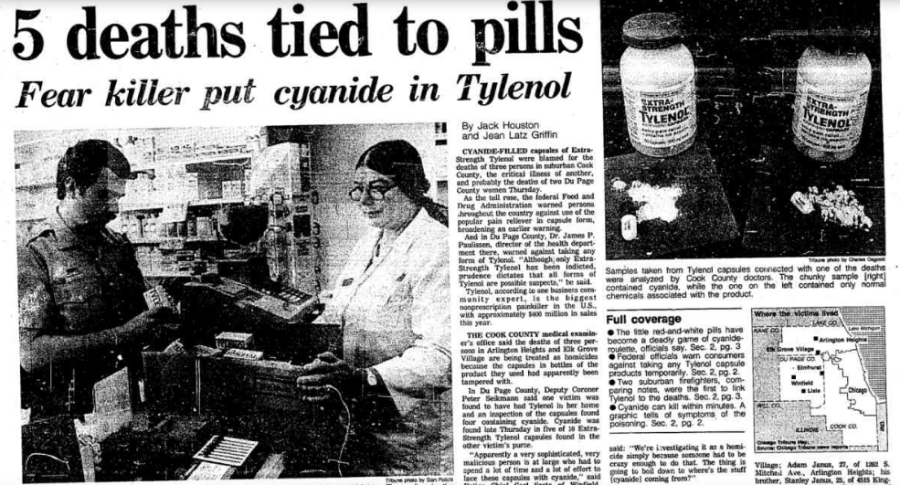

Psychologists called the killer of the Chicago Tylenol Poisonings so strange that their normal guidelines “just didn’t work.” Now, more than 26 years after Tylenol capsules laced with potassium cyanide killed seven people in the Chicago area, the Tylenol murders still have people scratching their heads. The FBI reopened the case and started taking a look at old suspects. With this case being reopened, it has enabled lots of old questions and concerns to resurface. There is no exact answer for all this madness, but it becomes more clear once we look into the reasoning behind these murders.

These attacks started in September 1982, when the parents of 12-year-old Mary Kellerman gave her a painkiller when she woke up complaining of a cold, and the young girl died hours later. Postal worker Adam Janus was also another victim who died in another Chicago Suburb later that morning. Janus’s brother and his brother’s wife complained of headaches while mourning Adam, who later died. In a few days, the death toll began to grow. The only link was that each victim had taken Extra Strength Tylenol. During testing, each of the capsules proved to be laced with potassium cyanide at a level toxic enough to provide thousands of fatal doses. Police were baffled since the pills came from different production plants and were sold in completely different drug stores around the Chicago area. They concluded that someone was most likely tampering with the drug on the store shelves.

The deaths set off a nationwide panic, as stores rushed to remove Tylenol from their shelves. They worried that customers overwhelmed hospitals and poison control hotlines. Chicago police also went through the streets with loudspeakers during this time. Johnson & Johnson, the drug manufacturer, spent millions of dollars recalling the pills from stores. The tampering of this medication inspired hundreds of copycat incidents across the United States. The Food and Drug Administration tallied more than 270 different incidents of product tampering in the month following the Tylenol deaths. Pills tainted with everything from fat poison to hydrochloric acid sickened people around the country, and some copycats even expanded to food tampering. During Halloween, parents reported finding sharp pins concealed in candy corn and candy bars. Some communities banned trick-or-treating altogether due to these incidents.

Police never arrested anyone for the original Tylenol murders, but tax consultant James Lewis wrote a letter to Tylenol’s manufacturer in October 1982 demanding $1 million to “stop the killings.” Lewis, however, had a strange past as well. He had been charged for the 1978 Kansas City Murder after police found the remains of one of his former clients in bags in his attic. All charges were dropped after a judge ruled that the police search of Lewis’ home was illegal, but police never tied him to the Tylenol killings and he denied committing them. Lewis was convicted of extortion for the letter and spent more than 12 years in federal prison.

Richard Brzezek, the Chicago police superintendent at the time, said it was unlikely Lewis would ever be prosecuted for the killings themselves. However, when the FBI reopened their investigation, the focus shifted back to Lewis. His Cambridge office was searched as well as a storage unit that he rented nearby. The FBI has been tight-lipped about the reason for the search and hasn’t named Lewis in conjunction with the reopened investigation. Police still have some of the tainted Tylenol capsules from the original killings and were hopeful that some DNA can be recovered from the pills for testing. The killings did have a measurable, positive impact, however: a revolution in product safety standards.

In the wake of the Tylenol poisonings, pharmaceutical and food industries dramatically improved their packaging. With this decision, they started instituting tamper-proof seals and indicators and increasing security controls during the manufacturing process. Although it may be of little solace to the families of the seven killed in Chicago, this resulted in a dramatic reduction in the number of copycat incidents. Thankfully now, as the FBI brings modern technology to cold cases, perhaps hope can be restored for something else tangible: at long last, some criminal charges.