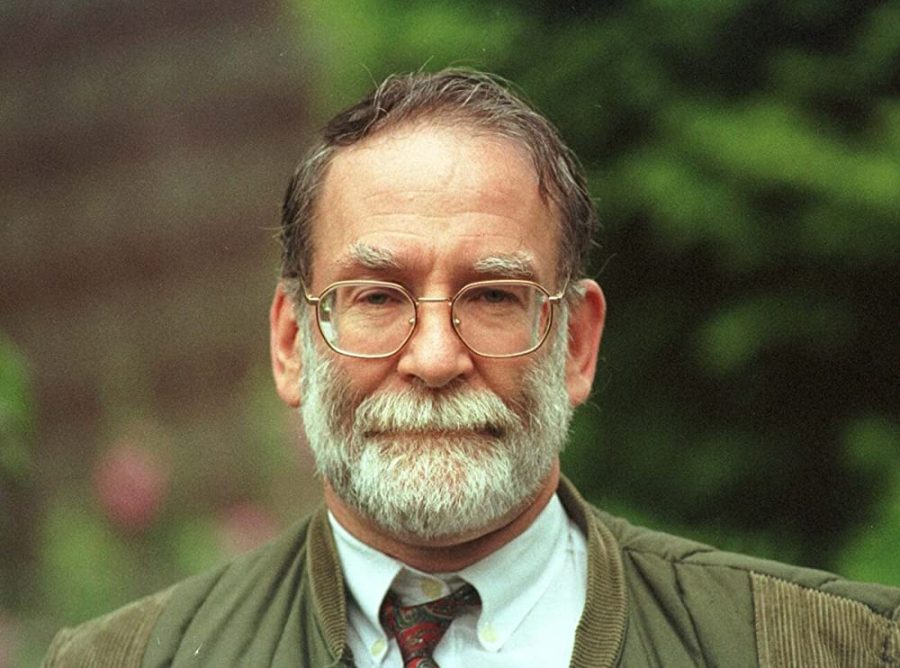

Harold Shipman

May 12, 2022

Born the middle child into a working-class family on January 14, 1946, Harold Fredrick Shipman, known as “Fred,” was the favorite child of his domineering mother, Vera. She instilled in him an early sense of superiority that tainted most of his later relationships, leaving him an isolated adolescent with few friends. When his mother was diagnosed with terminal lung cancer, he willingly oversaw her care as it declined, fascinated by the positive effect that the administration of morphine had on her suffering until she succumbed to the disease on June 21, 1963.

Devastated by her death, he was determined to go to medical school. He was admitted to Leeds University medical school for training before serving his hospital internship. He met his future wife, Primrose, at the age of 19, and they married when she was 17, five months pregnant with her child.

By 1974, he was a father of two and had joined a medical practice in Todmorden, Yorkshire, where he initially thrived as a family practitioner before allegedly becoming addicted to the painkiller Pethidine. He forged prescriptions for large amounts of the drug, and he was forced to leave the practice when caught by his medical colleagues in 1975. This was also the year that he entered a drug rehab program. In the subsequent inquiry, he received a small fine and a conviction for forgery.

A few years later, Shipman was accepted onto the staff at Donnybrook Medical Centre in Hyde, where he integrated himself as a hard-working doctor who enjoyed the trust of patients and colleagues alike. He remained on staff for almost two decades, and his behavior incurred only minor interest from other healthcare professionals.

The local undertaker noticed that Dr. Shipman’s patients seemed to be dying at an unusually high rate and exhibited similar poses in death: most were fully clothed, and usually sitting up or reclining on a settee. He was concerned enough to approach Shipman about this directly, who reassured him that there was nothing to be concerned about. Another medical colleague, Dr. Susan Booth, also found that similarity disturbing. The local coroner’s office was alerted and then contacted by the police.

A covert investigation followed, but Shipman was cleared, as it appeared that his records were in order. The inquiry failed to contact the General Medical Council or check criminal records, which would have yielded evidence of Shipman’s previous record. Later, a more thorough investigation revealed that Shipman altered the medical records of his patients to corroborate their causes of death.

Police later established that Shipman altered the medical notes directly after killing the patient to ensure that his account matched the historical records. What Shipman failed to grasp was that each alternation of the records would be time-stamped by the computer, this enabled police to ascertain exactly which records had been altered. Following extensive investigations, which included numerous examinations and autopsies, the police charged Shipman with 15 individual counts of murder on September 7, 1998, as well as one count of forgery.